A little noted two-liner in the newsfeed from Moscow sent shivers down the spine of gas experts – it means a lot both for Russian energy policies and for the EU’s energy market. The lines read that the interdepartmental commission on national security in economic and social affairs with the Security Council of the Russian Federation has decided to recommend the Russian Government revoke Gazprom’s monopoly on export of Russian gas to Europe.

This commission has consultative functions with the Security Council and reports to the Secretary of the Council Nikolay Patrushev. There have been many instances in the past of attempts from different business quarters in the Russian capital to press the government to allow more Russian gas producers to directly export their gas. The final say, as always, rests with President Putin, who until recently sided with Gazprom. The difference this time is that the issue has shifted into the highest “national security” gear and the Russian Security Council’s commission has said – it is time. The new US sanctions left the Kremlin with little space to maneuver in securing budget revenues from Russian gas sales to Europe – Gazprom’s are too vulnerable.

First, the EU gas market is shifting from long-term to shorter term spot contracts, mostly gas-to-gas benchmarked. This limits the extent to which the Russian state could help the national favorite – Gazprom – secure long-term oil-indexed contracts.

Second, Gazprom is too corpulent as a vehicle of Russian foreign policy. It attracts counteraction from the EU and the US, including sanctions that assist its competitors. The company’s unrivaled monopoly status in the EU has allowed it to be used for bullying the EU’s political circles into accommodating the Kremlin’s geopolitical ends, largely due to lack of credible alternative supplies. Russia can’t threaten anymore to cut gas supplies to EU member countries without damaging its long-term interests and market shares.

Supplies from the global LNG market and from alternative sources in the Black and Caspian Seas, Middle East, the East Mediterranean and Africa, plus a recently announced 30% increase in reserves of Statoil, Gazprom’s archrival in the EU market, in the Northern Sea, virtually deprive the Kremlin from using Russian gas as a foreign and energy policy tool. Therefore, Moscow is in dire need to adapt to an EU gas market that is shifting from seller-dominated to buyer-dominated. Demand rules.

The latest US sanctions further aggravate the existential paradigm of Russian oil and gas industries and the Russian budget. They are a direct hit on two of the key geopolitical projects in the Kremlin’s portfolio – Nord Stream and Turkish Stream, adding new pieces of uncertainty to the already overloaded chess board in the interplay between the European Commission and Gazprom. The final ruling on the anti-trust investigation against the Russian gas monopoly is still vague and the outcome is becoming less and less amenable to Russia’s wishes.

The European Commission managed to up the ante by requesting a mandate from all 28 EU member countries to negotiate with Gazprom over the compliance of Nord Stream with the EU’s energy directives. Failing to receive a consensus, with Germany and Austria clearly not set to grant this mandate, Brussels energy bureaucrats came up with the ingenious idea of suggesting that should Gazprom agree to let other Russian gas producers into Nord Stream, that will be considered as compliance.

This was not the final coup de grace to Gazprom’s export monopoly and direct support to Gazprom’s opponent in Russia, but it added weight to the US sanctions, tilting the balance at the Kremlin in favor of the revenues, sacrificing the export monopoly.

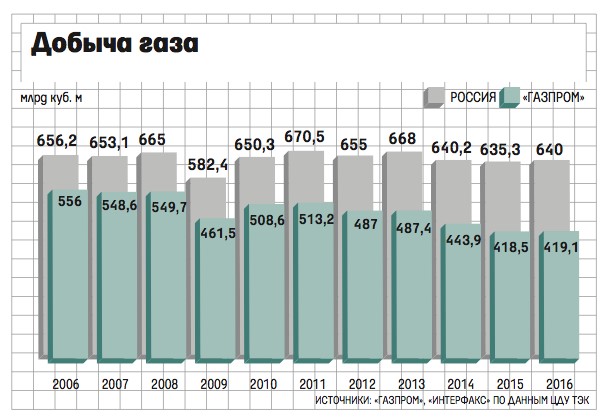

Figure 1 Russian Total/Gazprom Annual Gas Production

The independent gas producers in Russia are a force to be reckoned with, producing more than 210 billion cubic meters of gas, a significant chunk if it could end up with EU consumers. The difference between internal and international prices for Russian producers’ gas has earned Gazprom tens of billions of dollars. Two of the producers are pure gas companies – Northgas and Novatek – plus three are integrated oil companies with substantial gas output – Lukoil, Rosneft and, Surgutneftegaz.

In 2016 Gazprom bought more than 60 billion cubic meters of gas from independent producers at prices that were at least 2-3 times cheaper than the international market. Low oil prices make it harder for Gazprom’s competitors at home to recover the investments needed to sustain their upstream activity as well as their input into the state coffers.

The fight to dent Gazprom’s monopoly reached a turning point in 2014, when Novatek was given license to export its own produce via LNG terminals to the Asian markets. The EU market was left out of reach.

Rosneft’s powerful CEO Igor Sechin has been at the forefront of the opposition to Gazrpom’s monopoly. Yet Vladimir Putin has always been hesitant to relinquish his personal control on the financial cash flow and the power to navigate the Russian gas monopoly through the geopolitical troubled waters of Russian foreign policy. Worth recalling is that the Russian president has been ultra-sensitive to any Russian oligarch – worth recalling Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s fate – who has dared to engage in commercial deals with large global connotations for the Kremlin.

It is still too early to pass a final judgement on the fate of this recommendation. The fact that this Commission reviews it on national security grounds should not surprise anyone.

The fallout from licensing more Russian gas companies to export their gas to the EU market would be immense and immediate, long before their gas reaches EU consumers. At this stage, it is still premature to consider non-Gazprom gas as devoid of Kremlin influence or guidance. Putin’s grip would be equally tight on new exporters as with Gazprom. He would hardly allow open competition between the newcomers and Gazprom over gas prices in key EU markets. However, independents could complement and make up for any loss of market share in the short-term spot and long-term gas market – where the incumbent is unable to retain shares, including in eastern and southeastern Europe, where Gazprom is likely to lose substantial chunks of its almost 100% shares.

There are two more reasons the Kremlin might consider opening exports of Russian gas in earnest:

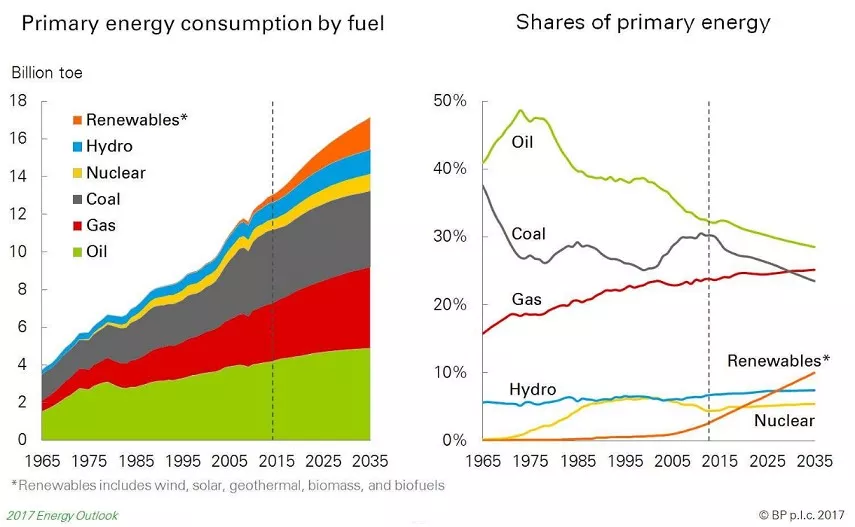

Demand for gas in Europe is relatively more predictable and projected to increase slightly, whereas oil demand is bound to fall. With the ban on fuel cars and the shift to less carbon intensive fuels as natural gas, this trend will certainly undermine the shares of oil and mostly coal companies in final energy consumption. Therefore, revenues from gas sales are more secure than from sales of oil. The shift of gas markets from oil indexation to gas-to-gas spot markets is a sure sign that the gas market is becoming self-sufficient, global and independent from the oil market.

Figure 2 Primary Energy Consumption and Shares

By allowing other Russian gas producers to directly access the EU market the Kremlin might be willing to give the EC ammunition to fight back ‘arrogant’ US sanctions, seeking to be seen as cooperative and willing to comply with EU guidance and energy directives.

The Kremlin feels it needs more options in the EU gas market than putting all the stakes on one horse – Gazprom. An end to Gazprom’s monopoly is likely to improve the chances of filling up Nord Stream and Turkish Stream with Russian gas from different producers. At least in theory.

However, the US sanctions, as they stand now, do not distinguish between restrictions on Gazprom and other Russian energy majors. Therefore, this move by the Security Council of the Russian Federation might be coming too late.

Link to original

Comments

Post a Comment